Recently in class we’ve been discussing the creation of online exhibits. We were asked this week to find an online exhibit from a public history institution and critique it, thinking about what works and what doesn’t work, what we’d change, etc. Many of my classmates chose to consider fancy (and probably expensive) exhibits created by institutions like the National Museum of American History or the National Portrait Gallery. I initially thought about critiquing an exhibit closer to home and looking at the online exhibits from the Women and Leadership Archives (WLA) or the University Archives here at Loyola. On more careful consideration, however, these institutions felt a little too close to home. After all, I do work at the WLA and personally know the people responsible for its two online exhibits. So I decided perhaps focusing on these exhibits wouldn’t be the best idea.

Instead, I decided to take my idea of closer to home literally and look for an institution in Ohio (my home state) that utilizes online exhibits. I was disappointed to find that the Western Reserve Historical Society does not have any online exhibits, so I instead looked to the Ohio Historical Society. Given the ridiculous winter we’ve had here in Chicago, and the even worse winter I know my family and friends in Ohio have been having, it seemed only fitting to explore the Ohio Historical Society’s exhibit Severe Weather in Ohio.

The exhibit is based on extreme weather events from the book Thunder in the Heartland: A Chronicle of Outstanding Weather Events in Ohio, by Dr. Thomas Schmidlin and Jeanne Appelhans Schmidlin. While the exhibit did not say when it was created, the book itself is nearly 20 years old, so I wonder if the exhibit itself is also older than many we might see today.

The first thing I noticed about the exhibit is the length of the introductory text. Weighing in at a whopping 753 words, saying there is too much text on this page would be a gross understatement. While the information provided on this page is interesting, much of it is not necessary. No one would design a physical exhibit with that much text at the beginning, so why would you design a digital exhibit that way? In addition, the exhibit content only took up about half of my laptop screen, with black space on either side. This just accentuated the overwhelming feeling of the text and made it seem even longer than it was.

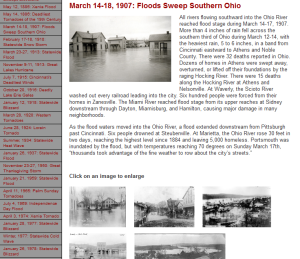

The introduction had me worried, would the rest of the exhibit be this wordy? Luckily, this was not the case. While I personally would have still cut down some of this text or attempted to break it up more with smaller paragraphs, the information on the individual events pages is much more manageable from a user standpoint. I liked that each page included at least one photograph, newspaper article, or drawing associated with the severe weather event which you can click to enlarge and read more about. Each page uses one graphic incorporated into the text in the top left corner and if there are other graphics they are provided all together at the bottom. I would have liked to see these images incorporated into the text as well to break up the flow and make it feel like they are actually part of the story, rather than simply extras. Additionally, this would have allowed for more creativity in the design of each page, making the exhibit more visually engaging.

This page of the exhibit discussing a 1907 flood would have been more interesting if the photos at the bottom had been integrated into the text.

I don’t mean to only be critical of this exhibit, because it is actually fascinating. Each page discusses what happened during this freak weather event, explores why it happened, and explains how the event affected the people of Ohio. From a hurricane on the Great Lakes in 1913 to the 28 tornadoes that ripped through Ohio in one day in 1992, the content of this exhibit is actually really interesting. I also like that the exhibit designers incorporated audio and video of these events when available. Another feature that I appreciated was the weather glossary which could be found on the top bar of every page. Clicking this link provided definitions of weather related terms used in the exhibit that visitors might need more explanation of.

From what I can tell, the main flaw in this exhibit is that it is old. I don’t know exactly when it was created, but I would guess it was at least 5 years ago and probably more like 10. For me, this begs the question when do digital exhibits end? While I did not attend the session at NCPH 2014 that discussed this very issue, I did see people discussing it on twitter and I found it intriguing. Physical exhibits, the presenter argued, have a definitive lifespan. Temporary exhibits have an obvious and easily quantified lifespan, but even permanent exhibits aren’t really permanent. These exhibits get revamped, have the objects rotated, and have new text written. Eventually, they are taken down and entire new permanent exhibits—even if only new in design rather than content—takes their place.

But what is the life cycle of a digital exhibit? Should there be a life cycle? I would argue yes. The digital world changes so quickly that an online exhibit will look old, worn out, and embarrassingly dated much sooner than a physical exhibit will. While it obviously takes additional time and money to redesign or replace online exhibits, it will ultimately create content that is more engaging for visitors and that encourages interaction.